Indigenous Foodways and Cultural Self-Determination: Reclaiming Identity Through Sustenance

Indigenous peoples across the globe share a profound and intrinsic connection to the land, a relationship that is deeply interwoven with their cultural identity, spiritual beliefs, and their very survival. At the heart of this connection lies their traditional foodways – the complex systems of knowledge, practices, and relationships surrounding the procurement, preparation, and consumption of food. In recent decades, a powerful movement has emerged, recognizing the vital role of indigenous food systems in achieving cultural self-determination. This movement asserts that the ability of indigenous communities to control, revitalize, and sustain their traditional diets is not merely a matter of food security, but a fundamental pathway to reclaiming their heritage, asserting their sovereignty, and fostering holistic well-being.

For millennia, indigenous communities developed sophisticated food systems perfectly adapted to their unique environments. These systems were not simply about calorie intake; they embodied intricate ecological knowledge, passed down through generations, encompassing sustainable harvesting techniques, understanding of plant and animal life cycles, and the interconnectedness of all living things. Traditional diets were rich in biodiversity, utilizing a vast array of local plants, animals, and fish, providing optimal nutrition and contributing to the resilience of both the people and the ecosystems they inhabited.

However, the devastating impact of colonization has profoundly disrupted these ancient foodways. The imposition of foreign agricultural practices, the forced displacement from ancestral lands, the introduction of processed and nutrient-poor foods, and the suppression of indigenous languages and cultural practices have led to a decline in traditional diets. This disruption has had dire consequences, contributing to rising rates of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and obesity within indigenous populations. Beyond the physical health impacts, the loss of traditional food practices has also eroded cultural knowledge, weakened social cohesion, and diminished a sense of identity and belonging.

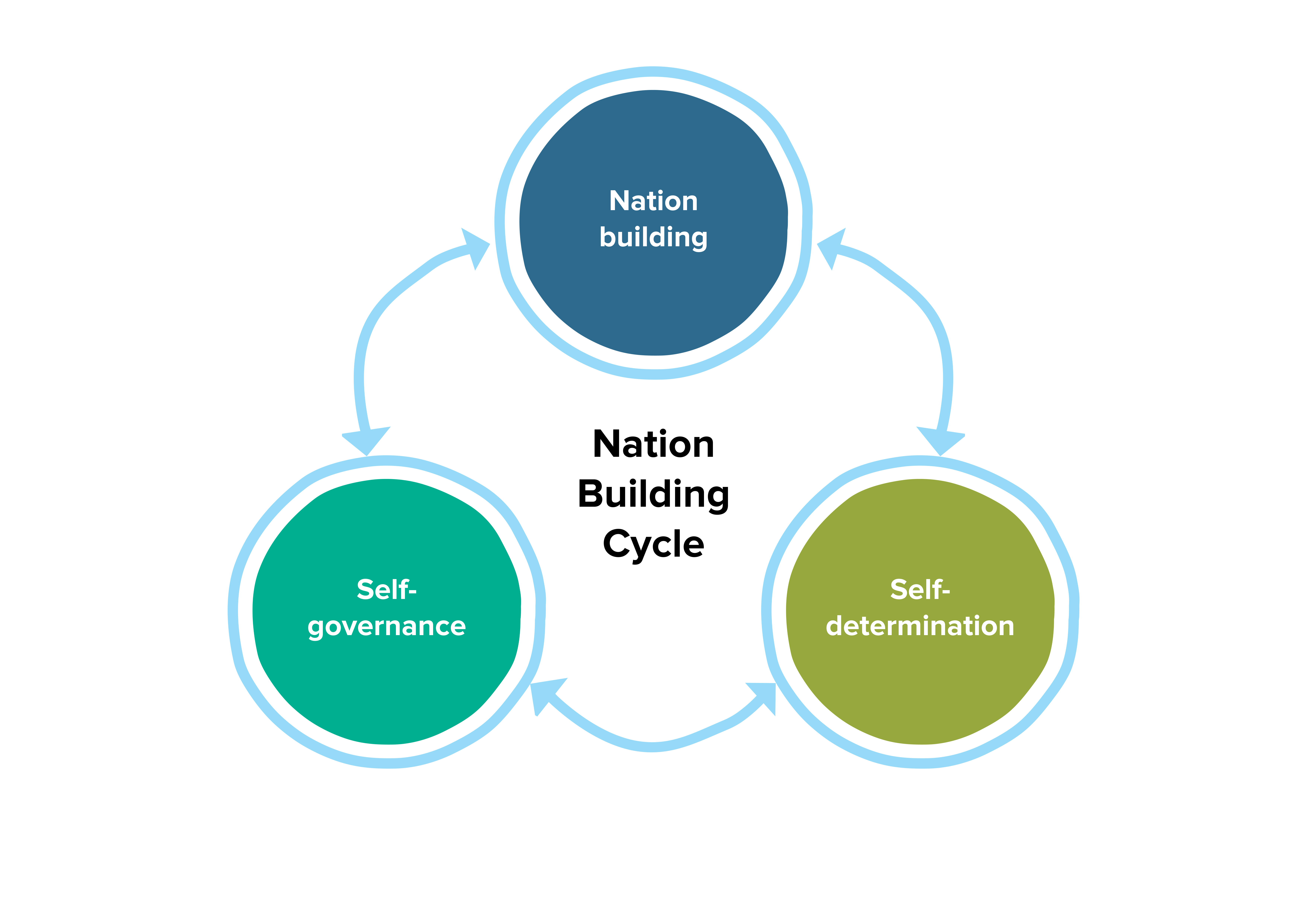

It is within this context that the concept of cultural self-determination through indigenous foodways gains immense significance. Cultural self-determination, in essence, refers to the right of indigenous peoples to define and practice their own culture, govern their own affairs, and determine their own future, free from external interference. When applied to food, it means indigenous communities having the autonomy to:

- Control their lands and waters: Access to and stewardship of ancestral territories is paramount for the sustainable harvesting of traditional foods.

- Revitalize traditional knowledge: Relearning and passing down the knowledge associated with foraging, hunting, fishing, agriculture, food preparation, and the cultural significance of specific foods.

- Control their food systems: Developing and managing their own food production, distribution, and consumption networks, free from the dominance of industrial food systems.

- Protect and promote their food heritage: Safeguarding traditional recipes, food preparation techniques, and the cultural narratives surrounding food.

- Make informed choices about their diets: Having access to and the ability to choose traditional foods over unhealthy, processed alternatives.

The reclamation of indigenous foodways is a multi-faceted endeavor, involving a range of strategies and initiatives. One of the most visible aspects is the revitalization of traditional foods. This can involve:

- Seed saving and traditional agriculture: Communities are actively working to preserve and reintroduce heritage seeds and traditional farming methods, ensuring the continued availability of native crops.

- Sustainable harvesting and hunting: Educating younger generations about ethical and sustainable practices for gathering wild foods, hunting, and fishing, ensuring the long-term health of ecosystems.

- Foraging and wildcrafting: Reconnecting with the knowledge of edible wild plants, berries, and mushrooms, often overlooked by modern society.

- Cultivating indigenous gardens: Establishing community gardens and backyard plots dedicated to growing traditional crops.

Beyond the physical act of growing and harvesting, food sovereignty is a crucial component. Food sovereignty goes beyond food security (ensuring access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food) by emphasizing the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through sustainable methods and their own food systems. This involves:

- Community-led food initiatives: Establishing food banks, community kitchens, and farmers’ markets that prioritize indigenous foods and producers.

- Developing local food economies: Creating opportunities for indigenous entrepreneurs to market and sell their traditional foods, fostering economic independence.

- Advocacy and policy change: Working to influence government policies that support indigenous food systems, protect traditional food resources, and address the systemic inequities that have led to food insecurity.

- Education and cultural transmission: Integrating traditional food knowledge into school curricula, workshops, and intergenerational learning programs.

The connection between indigenous food and cultural self-determination is deeply spiritual and social. Food is not just sustenance; it is a vehicle for storytelling, ceremony, and community bonding. Sharing traditional meals strengthens social ties, reinforces cultural values, and provides a sense of continuity with ancestors. When indigenous communities can gather to prepare and eat foods that have sustained them for generations, they are actively asserting their right to their cultural identity and heritage.

Consider the profound significance of a community feast featuring wild salmon, harvested sustainably from ancestral fishing grounds, or a gathering where elders share stories and traditional recipes for bannock or wild rice. These are not simply meals; they are acts of cultural affirmation, of resistance against assimilation, and of the powerful assertion of self-determination.

Furthermore, the intellectual property associated with traditional food knowledge is increasingly being recognized and protected. This includes safeguarding the genetic diversity of indigenous crops and the cultural knowledge surrounding their cultivation and use, preventing their exploitation by external entities.

In conclusion, the reclamation and revitalization of indigenous foodways are integral to the ongoing struggle for cultural self-determination. By regaining control over their food systems, indigenous communities are not only addressing critical health disparities but are also actively rebuilding their cultural foundations, strengthening their identities, and asserting their inherent right to govern their own lives and futures. The journey towards true self-determination is deeply rooted in the earth, nurtured by ancestral wisdom, and shared through the profound act of nourishing oneself and one’s community with the foods that have always been, and will always be, theirs.

Sample Indigenous Recipes

Here are a few sample recipes that reflect the spirit of indigenous foodways. It’s important to note that "Indigenous food" is incredibly diverse, with each nation and region having its unique culinary traditions. These are simplified examples and often can be adapted based on available ingredients and regional variations.

1. Wild Rice Salad with Berries and Toasted Seeds (Inspired by Ojibwe/Anishinaabe traditions)

Wild rice (Manoomin) is a sacred and staple grain for many Indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes region.

Yields: 4-6 servings

Prep time: 20 minutes

Cook time: 45-60 minutes (for wild rice)

Ingredients:

- 1 cup wild rice, rinsed

- 2 cups water or vegetable broth

- 1/4 cup dried cranberries or blueberries

- 1/4 cup fresh berries (e.g., blueberries, raspberries, Saskatoons if available)

- 1/4 cup toasted pumpkin seeds (pepitas) or sunflower seeds

- 1/4 cup chopped fresh parsley or mint

- 2 tablespoons olive oil

- 1 tablespoon lemon juice or apple cider vinegar

- Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

Instructions:

- Cook the Wild Rice: In a medium saucepan, combine the rinsed wild rice and water/broth. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat to low, cover, and simmer for 45-60 minutes, or until the rice is tender and has "bloomed" (opened up). Drain any excess liquid. Let the wild rice cool completely.

- Toast Seeds: While the rice is cooking or cooling, toast the pumpkin or sunflower seeds in a dry skillet over medium heat until fragrant and lightly browned. Watch them closely to prevent burning.

- Assemble the Salad: In a large bowl, combine the cooled wild rice, dried cranberries, fresh berries, toasted seeds, and chopped parsley/mint.

- Make the Dressing: In a small bowl, whisk together the olive oil, lemon juice/vinegar, salt, and pepper.

- Dress and Serve: Pour the dressing over the salad and toss gently to combine. Taste and adjust seasoning if needed. Serve chilled or at room temperature.

2. Bannock (Traditional Indigenous Quick Bread)

Bannock is a versatile and simple bread that has been a staple for many Indigenous peoples across North America, adapted from traditional baking methods.

Yields: 1 large bannock or 8-10 small bannocks

Prep time: 10 minutes

Cook time: 20-30 minutes

Ingredients:

- 2 cups all-purpose flour

- 2 teaspoons baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 2 tablespoons lard, shortening, or butter, chilled and cut into small pieces (or 2 tablespoons vegetable oil for a simpler version)

- 3/4 cup water, milk, or buttermilk (add more as needed)

Instructions:

Pan-Fried Bannock (Traditional Method):

- Mix Dry Ingredients: In a bowl, whisk together the flour, baking powder, and salt.

- Cut in Fat: Add the chilled lard/shortening/butter and rub it into the dry ingredients with your fingertips until the mixture resembles coarse crumbs. If using oil, simply stir it in.

- Add Liquid: Gradually add the liquid, stirring until a soft dough forms. Add more liquid if it seems too dry, or a little more flour if it’s too sticky.

- Form the Bannock: Turn the dough out onto a lightly floured surface and gently knead for a minute or two until it just comes together. Do not overwork. Form into a round, flattened disc (about 1-inch thick).

- Fry the Bannock: Heat about 1/2 inch of cooking oil or lard in a cast-iron skillet over medium heat. Carefully place the bannock disc into the hot oil. Fry for about 8-12 minutes per side, until golden brown and cooked through. You may need to reduce the heat slightly to ensure the inside cooks without burning the outside.

- Drain and Serve: Remove the bannock from the skillet and drain on paper towels. Serve warm, often with butter, jam, or honey.

Baked Bannock:

- Follow steps 1-4 above.

- Place the dough disc on a greased baking sheet or in a greased cast-iron skillet.

- Bake in a preheated oven at 375°F (190°C) for 20-30 minutes, or until golden brown and cooked through.

3. Smoked Fish (General Principle)

Smoking fish is a traditional preservation and cooking method for many Indigenous communities. The specific fish and smoking techniques vary widely.

Ingredients:

- Fresh, whole fish (e.g., salmon, trout, whitefish), cleaned and gutted

- Brine (optional, for flavor and preservation): Water, salt, and optionally sugar, herbs, or spices.

Instructions (General Outline):

- Prepare the Fish: Clean and gut the fish thoroughly. Some recipes call for splitting the fish open from the back (butterfly cut), while others leave it whole.

- Brine (Optional): If brining, prepare a solution of water and salt (e.g., 1/4 cup salt per quart of water). Submerge the fish in the brine for a few hours to overnight, depending on the size of the fish. Rinse thoroughly after brining.

- Dry the Fish: Pat the fish very dry with paper towels. Allow the fish to air dry in a cool, well-ventilated area for a few hours until a pellicle (a slightly sticky surface) forms. This helps the smoke adhere better.

- Prepare the Smoker: Use a cold smoker or a hot smoker. For cold smoking, the temperature is kept low (below 80°F/27°C) to preserve the fish and impart flavor over many hours or days. For hot smoking, the temperature is higher, cooking the fish while smoking it.

- Smoke the Fish: Place the prepared fish in the smoker. Use hardwoods like alder, maple, or fruitwoods for smoking. The smoking time will vary greatly depending on the type of smoker, temperature, and size of the fish.

- Check for Doneness: Smoked fish is typically cooked through when it flakes easily with a fork.

- Serve: Smoked fish can be eaten as is, flaked into salads, or served with traditional accompaniments.

These recipes are starting points. The true essence of indigenous food lies in the stories, the cultural practices, and the deep connection to the land that surrounds them.