Absolutely! Here’s an article on Indigenous Food and Cultural Awareness, along with a few recipe examples.

Nourishing Roots: Indigenous Food and the Cultivation of Cultural Awareness

The aroma of woodsmoke, the earthy scent of freshly harvested roots, the vibrant hues of sun-ripened berries – these are the sensory touchstones of Indigenous food systems. Far more than mere sustenance, these culinary traditions are intricate tapestries woven with generations of knowledge, spiritual connection to the land, and profound cultural identity. In a world increasingly disconnected from its food sources, understanding and appreciating Indigenous foodways offers a vital pathway to fostering cultural awareness, promoting ecological stewardship, and revitalizing ancestral wisdom.

For millennia, Indigenous peoples across the globe have developed sophisticated and sustainable food systems, deeply attuned to the rhythms of their respective environments. These systems are not static relics of the past; they are living, breathing expressions of cultural resilience and adaptation. From the vast plains where bison roamed freely to the coastal waters teeming with life, and the ancient forests yielding a bounty of plant and animal resources, Indigenous diets reflect an intimate understanding of local ecosystems. This understanding encompasses not only what to eat but also how to harvest, prepare, and preserve food in a way that ensures the health of the land for future generations.

Beyond the Plate: The Cultural Significance of Indigenous Food

The importance of Indigenous food extends far beyond its nutritional value. Food is intrinsically linked to identity, community, and spirituality. For many Indigenous cultures, specific foods hold deep symbolic meaning, playing crucial roles in ceremonies, rituals, and storytelling. The act of preparing and sharing a meal is often a communal experience, reinforcing social bonds and transmitting cultural knowledge. Elders, as keepers of ancestral wisdom, play a pivotal role in teaching younger generations about traditional foods, their preparation, and the stories and protocols associated with them.

Consider the Wampum of the Eastern Woodlands, a string of shell beads that served not only as a record of treaties and historical events but also symbolized the interconnectedness of life, including the sustenance provided by the land and water. Or the corn, beans, and squash, collectively known as the "Three Sisters," a symbiotic planting system that not only provides a balanced diet but also embodies principles of cooperation and mutual support. These are not just agricultural techniques; they are philosophical frameworks for living in harmony with nature.

The arrival of European colonizers had a devastating impact on Indigenous food systems. Traditional lands were seized, traditional hunting and gathering practices were disrupted, and Indigenous peoples were often forced to adopt unfamiliar and less nutritious diets. This disruption led to a loss of cultural knowledge, a decline in health, and a fracturing of communities. However, the resilience of Indigenous peoples has meant that many of these food traditions have survived, and in recent decades, there has been a powerful resurgence of interest in revitalizing and celebrating Indigenous cuisine.

Revitalizing Traditions: The Modern Movement

Today, Indigenous chefs, food activists, farmers, and community leaders are at the forefront of a movement to reclaim and reassert their ancestral foodways. This revitalization is multifaceted. It involves:

- Reclaiming Traditional Knowledge: Actively seeking out and documenting traditional food practices, plant and animal species, and preparation methods from elders and community members.

- Sustainable Harvesting and Agriculture: Re-introducing and expanding traditional farming techniques, such as the Three Sisters method, and promoting sustainable harvesting practices that respect ecological limits.

- Seed Saving and Biodiversity: Protecting and propagating heirloom seeds and native plant species that are vital for maintaining biodiversity and food security.

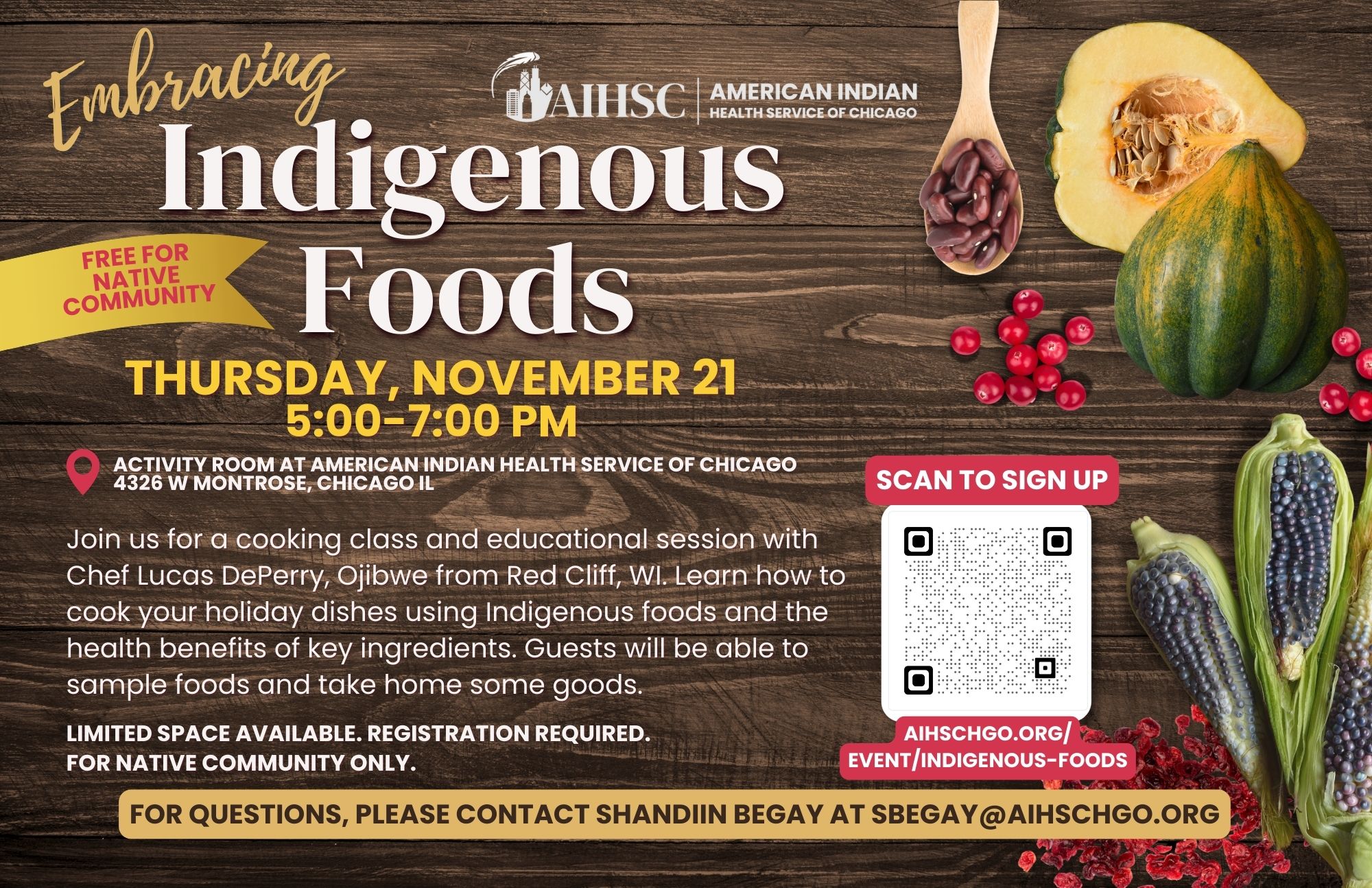

- Cultural Exchange and Education: Sharing Indigenous food knowledge with broader society through culinary events, workshops, and educational programs, fostering understanding and respect.

- Economic Empowerment: Creating opportunities for Indigenous communities to benefit economically from their traditional food systems through sustainable agriculture, tourism, and food businesses.

This movement is not just about preserving the past; it’s about building a more sustainable and equitable food future. Indigenous food systems often embody principles of ecological sustainability, low-impact agriculture, and a deep respect for natural resources. By learning from these traditions, we can gain valuable insights into how to live more harmoniously with the planet.

Understanding Through Taste: Recipes as Cultural Bridges

One of the most accessible and enjoyable ways to engage with Indigenous food and cultural awareness is through experiencing the food itself. While it’s crucial to acknowledge that recipes vary widely across hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations and cultures, and that authentic preparation often involves specific ancestral knowledge and ingredients not always readily available, exploring representative recipes can offer a glimpse into these rich traditions.

It’s important to approach these recipes with respect and an understanding that they are simplified representations. The true essence lies in the connection to the land, the stories embedded within the ingredients, and the communal act of preparation and sharing.

Recipe Examples:

Here are a few examples of dishes that highlight key elements of Indigenous cuisine. Please remember to research the specific cultural context and origins of any dish you wish to prepare and, if possible, learn from Indigenous individuals or communities.

1. Three Sisters Stew (Nourishing & Symbolic)

This stew represents the harmonious relationship between corn, beans, and squash, a cornerstone of many Indigenous agricultural systems. It’s a hearty and nutritious dish.

Ingredients:

- 1 tablespoon cooking oil (traditionally rendered animal fat might have been used)

- 1 large onion, chopped

- 2 cloves garlic, minced

- 1 pound stewing meat (such as venison, bison, or beef), cut into cubes

- 4 cups vegetable or game broth

- 1 cup dried kidney beans or black beans, soaked overnight and drained

- 1 cup corn kernels (fresh or frozen)

- 1 cup diced butternut squash or pumpkin

- 1 teaspoon dried sage

- 1 teaspoon dried thyme

- Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

- Fresh parsley or cilantro, chopped, for garnish

Instructions:

- Heat oil in a large pot or Dutch oven over medium-high heat. Brown the meat on all sides. Remove meat and set aside.

- Add onion to the pot and cook until softened, about 5 minutes. Add garlic and cook for 1 minute more until fragrant.

- Return the meat to the pot. Add broth and soaked beans. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat, cover, and simmer for 1-1.5 hours, or until the meat is tender.

- Add the corn and squash to the pot. Stir in sage and thyme.

- Continue to simmer, uncovered, for another 20-30 minutes, or until the squash is tender and the stew has thickened.

- Season with salt and pepper to taste.

- Serve hot, garnished with fresh herbs.

Cultural Note: This dish embodies cooperation. The corn provides a stalk for the beans to climb, the beans fix nitrogen in the soil, and the squash’s broad leaves shade the ground, retaining moisture and suppressing weeds.

2. Wild Rice Pilaf with Berries and Nuts (Earthy & Sweet)

Wild rice is a sacred grain for many Indigenous peoples of North America, particularly in the Great Lakes region. This pilaf highlights its nutty flavor with the sweetness of berries and the crunch of nuts.

Ingredients:

- 1 cup wild rice, rinsed

- 2 cups water or vegetable broth

- 1 tablespoon butter or cooking oil

- 1/2 cup chopped wild onions or leeks (or regular onion)

- 1/4 cup dried cranberries or blueberries

- 1/4 cup toasted pecans or walnuts, chopped

- Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

Instructions:

- In a medium saucepan, combine the rinsed wild rice and water or broth. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat, cover, and simmer for 45-60 minutes, or until the rice is tender and has "popped" open. Drain any excess liquid.

- While the rice is cooking, melt butter or heat oil in a small skillet over medium heat. Add chopped onions and cook until softened, about 5 minutes.

- In a bowl, combine the cooked wild rice, sautéed onions, dried berries, and toasted nuts.

- Season with salt and pepper to taste. Gently toss to combine.

- Serve as a side dish or a light main course.

Cultural Note: Wild rice harvesting is a traditional practice deeply connected to water and the cycles of nature. It’s often gathered by canoe, using a pole to knock the grains into the canoe.

3. Bannock (Simple & Versatile)

Bannock is a type of unleavened bread found in various Indigenous cultures, often adapted to available ingredients. It can be baked, fried, or cooked over an open fire.

Ingredients:

- 2 cups all-purpose flour

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 cup shortening or lard (or butter)

- About 3/4 cup milk or water (adjust for consistency)

Instructions (Baked Version):

- Preheat oven to 375°F (190°C). Grease a baking sheet or line with parchment paper.

- In a large bowl, whisk together flour, baking powder, and salt.

- Cut in the shortening or lard using your fingertips or a pastry blender until the mixture resembles coarse crumbs.

- Gradually add milk or water, stirring until a soft dough forms. Do not overmix.

- Turn the dough out onto a lightly floured surface and gently knead a few times until it just comes together.

- Pat or roll the dough into a round or oval shape, about 1/2 to 3/4 inch thick.

- Place the dough on the prepared baking sheet.

- Bake for 20-25 minutes, or until golden brown and cooked through.

- Let cool slightly before slicing. Serve warm, perhaps with jam or butter.

Cultural Note: Bannock was historically made with flour provided through trade or rations, making it a staple that could be prepared with minimal cooking facilities. It’s a symbol of resourcefulness and adaptability.

Fostering Cultural Awareness Through Indigenous Food

Engaging with Indigenous food is an act of learning, respect, and solidarity. It’s an invitation to understand the profound connection between people, place, and sustenance. By seeking out Indigenous-led initiatives, supporting Indigenous food producers, and educating ourselves about the history and cultural significance of these traditions, we can contribute to the ongoing revitalization and preservation of these invaluable culinary heritages.

This journey into Indigenous foodways is not just about discovering new flavors; it’s about recognizing the wisdom of ancestral knowledge, celebrating the resilience of cultures, and cultivating a deeper awareness of our interconnectedness with the natural world. It’s about nourishing not just our bodies, but our understanding and our respect for the diverse and vibrant tapestry of human experience.