The Living Legacy: Indigenous Food and Intergenerational Knowledge Transfer

The vibrant tapestry of human culture is intricately woven with threads of sustenance. Among the most profound and enduring of these threads are the culinary traditions of Indigenous peoples worldwide. Far more than mere recipes, Indigenous foods represent a deep, symbiotic relationship with the land, a complex understanding of ecology, and a rich repository of intergenerational knowledge. This knowledge, passed down through stories, practices, and lived experiences, is not just about what to eat, but how to eat, when to eat, and why certain foods are important to the identity and well-being of a community.

Indigenous food systems are characterized by their seasonality, sustainability, and profound respect for natural resources. They are a testament to centuries of observation, experimentation, and adaptation. The preparation and consumption of these foods are not isolated acts but are embedded within a broader cultural context, often tied to ceremonies, social gatherings, and spiritual beliefs. This holistic approach ensures that the knowledge surrounding food is not confined to the kitchen but permeates all aspects of life.

The transfer of this knowledge from one generation to the next is a dynamic and crucial process. It is a living legacy, constantly evolving yet deeply rooted in tradition. This intergenerational transfer is not a passive absorption of information but an active engagement. Elders, the keepers of this wisdom, play a pivotal role. They share their knowledge through hands-on mentorship, storytelling, guided foraging expeditions, and the meticulous demonstration of traditional preparation techniques. Young people learn not only the ingredients and methods but also the cultural significance, the medicinal properties, and the ethical considerations associated with harvesting and consuming specific foods.

Consider the art of foraging. An elder might take a child into the forest, not just to point out edible plants, but to teach them how to identify them, understand their growth cycles, the soil conditions they prefer, and the ecological role they play. They learn to harvest sustainably, taking only what is needed, ensuring the plant can regenerate, and respecting the spirits of the land. This is a far cry from modern agriculture, where the focus is often on maximizing yield with little regard for the long-term health of the ecosystem.

Storytelling is another powerful vehicle for knowledge transfer. Many Indigenous cultures have creation stories, legends, and historical accounts that are inextricably linked to food. These narratives explain the origins of certain plants and animals, the importance of particular foods in times of scarcity, and the moral lessons associated with their use. These stories imbue food with meaning beyond its nutritional value, fostering a sense of connection to ancestors, the land, and the spiritual realm.

The skills learned through intergenerational knowledge transfer extend beyond simple cooking. They encompass a deep understanding of food preservation techniques, such as smoking, drying, fermenting, and salting, which were essential for survival in pre-refrigeration eras. These methods not only extended the shelf life of food but also often enhanced its flavor and nutritional content. The ability to transform raw ingredients into nourishing and culturally significant meals was a vital skill, ensuring the continuity of communities.

However, this vital intergenerational knowledge transfer is facing significant challenges in the modern era. Colonization, displacement, the imposition of Western diets, and the disruption of traditional land-use practices have all contributed to the erosion of Indigenous food systems and the knowledge associated with them. The availability of processed foods, often cheaper and more accessible, has led to dietary shifts that can have detrimental health consequences for Indigenous communities, contributing to higher rates of chronic diseases.

The loss of language is also a major impediment. Many Indigenous languages contain specific terms for plants, animals, and their uses that are not easily translated. When languages are lost, so too is a significant portion of the nuanced knowledge embedded within them. The younger generations, often immersed in dominant cultures, may not have the same opportunities to learn from elders in their traditional languages, leading to a disconnect from their heritage.

Despite these challenges, there are inspiring efforts underway to revitalize Indigenous food systems and ensure the continuity of intergenerational knowledge. Indigenous communities are actively working to reclaim their traditional lands, re-establish sustainable harvesting practices, and promote the cultivation of native crops. Food sovereignty movements are gaining momentum, empowering communities to control their own food systems and ensure access to healthy, culturally appropriate foods.

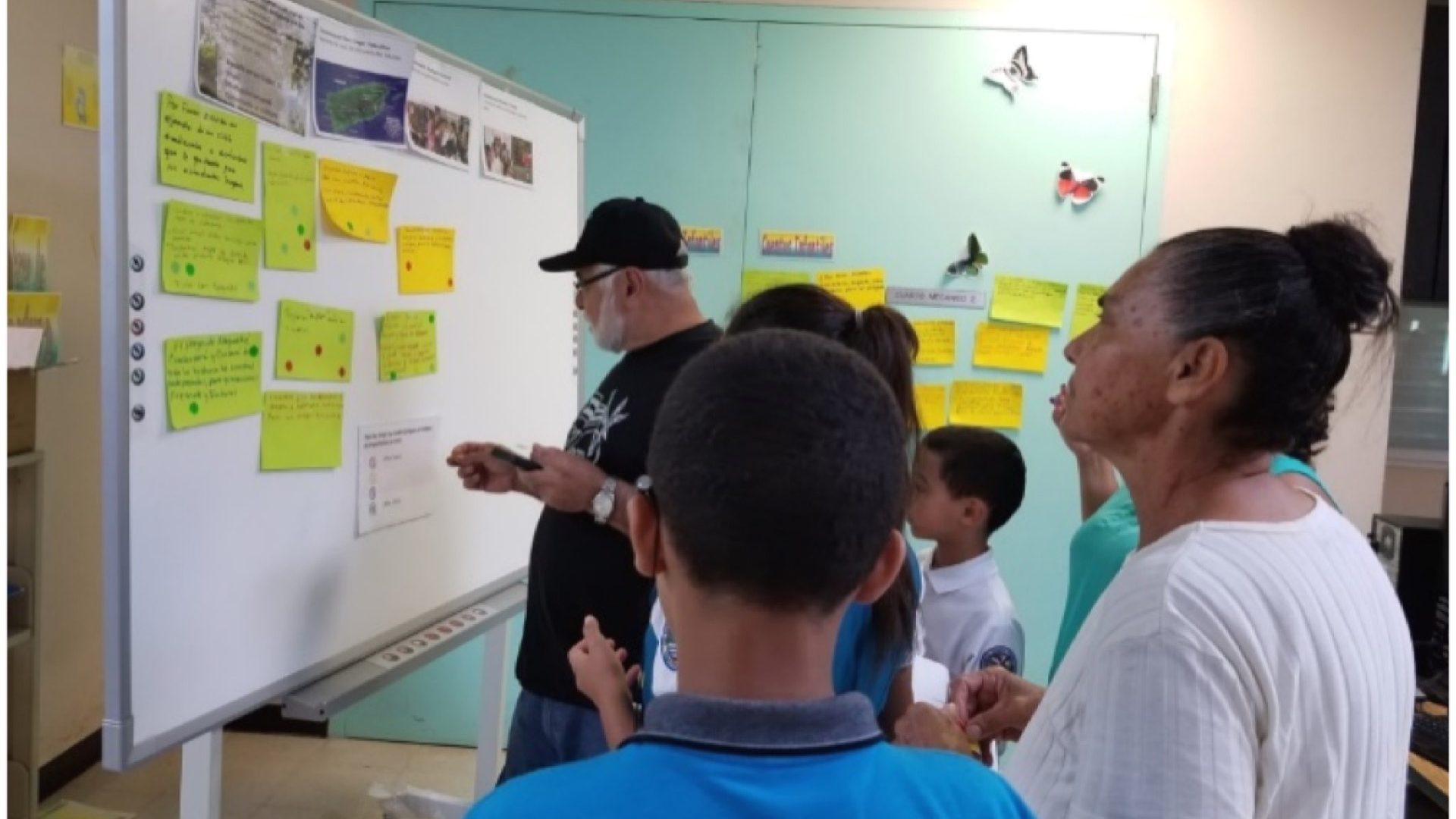

Educational initiatives are playing a crucial role. Schools are incorporating Indigenous food knowledge into their curricula, teaching students about native plants, traditional cooking methods, and the importance of food security. Elders are being invited to share their expertise in classrooms and community centers, bridging the gap between generations. Cultural festivals and events that celebrate Indigenous foods are becoming vital platforms for knowledge sharing and community building.

The digital age, while presenting its own challenges, also offers new avenues for knowledge transfer. Online resources, documentaries, and social media platforms are being used to document and disseminate Indigenous food knowledge to a wider audience, both within and outside Indigenous communities. This can help raise awareness and foster appreciation for these rich culinary traditions.

Ultimately, the preservation and revitalization of Indigenous food systems and the intergenerational knowledge they embody are not just about culinary heritage; they are about cultural survival, ecological stewardship, and the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples. It is a testament to resilience and the enduring power of connection – connection to the land, to ancestors, and to each other. By supporting these efforts, we contribute to a more just, sustainable, and culturally rich world.

Sample Indigenous Recipes: A Taste of Heritage

While specific recipes vary greatly among the diverse Indigenous cultures of the world, here are a few representative examples that showcase the principles of traditional preparation and ingredient use. These are simplified versions, and it’s important to remember that true authenticity lies in the knowledge and practices passed down through generations.

1. Pemmican (North American Plains Indigenous Peoples)

Pemmican is a highly nutritious, shelf-stable food that was a staple for many Indigenous peoples of the North American Plains. It’s a concentrated source of protein and fat, ideal for long journeys and periods of scarcity.

Ingredients:

- Lean dried meat (traditionally bison, venison, or elk), finely pounded into a powder or coarse meal.

- Rendered animal fat (tallow), traditionally from the same animal.

- Optional: Dried berries (e.g., chokecherries, blueberries) for flavor and added nutrients.

Instructions:

- Prepare the Meat: Ensure the dried meat is thoroughly pounded into a fine powder or coarse meal. This can be done using a mortar and pestle or by placing it in a strong bag and pounding with a heavy object.

- Render the Fat: Gently heat the animal fat in a pot until it melts into a liquid. Strain out any solid impurities.

- Combine Ingredients: In a bowl, combine the pounded dried meat with the melted fat. The ratio of meat to fat is typically 1:1, but can be adjusted based on preference and intended use.

- Add Berries (Optional): If using dried berries, gently crush them and mix them into the pemmican mixture.

- Mix Thoroughly: Mix the ingredients vigorously until the meat powder is completely coated with fat. The mixture should hold together when squeezed.

- Shape and Store: Shape the pemmican into blocks, balls, or bars. Traditionally, it was often wrapped in animal hide or packed into bags. Allow it to cool and harden. Store in a cool, dry place.

Intergenerational Knowledge: Elders taught the importance of lean meat for energy and fat for sustained sustenance. The pounding and rendering techniques ensured maximum nutrient extraction and preservation. The ability to create pemmican was vital for survival during hunting expeditions and winter months.

2. Three Sisters Stew (Haudenosaunee and other Northeastern Indigenous Peoples)

The "Three Sisters" refers to the complementary planting of corn, beans, and squash, a sophisticated agricultural system that sustained many Indigenous communities. This stew embodies the nutritional synergy of these crops.

Ingredients:

- 1 cup dried or fresh corn kernels (or 2 cups fresh corn cut from the cob)

- 1 cup dried or fresh beans (e.g., pinto beans, kidney beans, or specific Indigenous varieties), soaked overnight if dried

- 1 medium squash (e.g., butternut, acorn), peeled, seeded, and cubed

- 1 onion, chopped

- 2-3 cloves garlic, minced

- 4-6 cups vegetable broth or water

- Herbs: Wild rice (optional), thyme, sage, or other native herbs to taste

- Salt and pepper to taste

- Optional: Smoked meat or fish for added flavor and protein.

Instructions:

- Cook Beans: If using dried beans, rinse them and cook them in water until tender. If using canned beans, rinse them thoroughly.

- Sauté Aromatics: In a large pot or Dutch oven, sauté the chopped onion and minced garlic in a little oil or rendered fat until softened.

- Add Squash and Corn: Add the cubed squash and corn kernels to the pot. Stir to combine with the aromatics.

- Add Broth and Beans: Pour in the vegetable broth or water, ensuring all ingredients are submerged. Add the cooked beans.

- Simmer: Bring the stew to a boil, then reduce heat, cover, and simmer for 30-45 minutes, or until the squash is tender and the flavors have melded.

- Add Herbs and Seasoning: Stir in your chosen herbs (like wild rice, thyme, or sage). Season with salt and pepper to taste. If using smoked meat or fish, add it during the last 15-20 minutes of simmering.

- Serve: Ladle the hot stew into bowls.

Intergenerational Knowledge: This dish highlights the ecological intelligence of companion planting. Corn provides a trellis for beans, beans fix nitrogen in the soil, and squash’s broad leaves suppress weeds and retain moisture. The stew itself demonstrates how to combine these staple crops for a complete and balanced meal, often passed down through oral tradition and communal cooking.

3. Smoked Salmon with Wild Berries (Pacific Northwest Indigenous Peoples)

The Pacific Northwest is renowned for its rich salmon runs and abundant wild berries. Smoking and drying were essential preservation methods, and the pairing of savory salmon with sweet berries is a classic combination.

Ingredients:

- Fresh salmon fillets, skin on (or whole cleaned salmon)

- Salt (for brining, optional)

- Wood chips for smoking (e.g., alder, maple, fruitwood)

- Assorted fresh or dried wild berries (e.g., huckleberries, salmonberries, blueberries)

- Optional: A drizzle of maple syrup or honey for serving.

Instructions:

- Prepare the Salmon: Rinse the salmon fillets and pat them dry. For enhanced flavor and preservation, you can brine the salmon in a saltwater solution (e.g., 1 cup salt to 4 cups water) for a few hours, then rinse and pat dry.

- Prepare the Smoker: Set up your smoker according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Soak your wood chips in water for at least 30 minutes, then drain.

- Smoke the Salmon: Place the salmon, skin-side down, on the smoker racks. Add the soaked wood chips to the heat source. Smoke the salmon at a low temperature (around 150-175°F or 65-80°C) for several hours, or until the salmon is cooked through and has a firm texture. The skin should be slightly crispy, and the flesh should flake easily.

- Prepare the Berries: If using fresh berries, gently rinse them. If using dried berries, they can be rehydrated slightly in warm water if desired.

- Serve: Serve the warm or room-temperature smoked salmon alongside a generous portion of wild berries. A light drizzle of maple syrup or honey can complement the flavors beautifully.

Intergenerational Knowledge: This recipe represents generations of knowledge about fishing, smoking, and foraging. Elders understood the best fishing times, the properties of different smoking woods, and the seasonal availability of berries. The ability to preserve salmon through smoking ensured a vital food source throughout the year, and the pairing with berries added essential vitamins and natural sweetness.

These recipes are just a glimpse into the vast and diverse world of Indigenous cuisine. They offer a tangible connection to the deep ecological understanding, cultural richness, and enduring wisdom of Indigenous peoples.