The Sustaining Roots: Indigenous Foodways and Traditional Ecological Knowledge

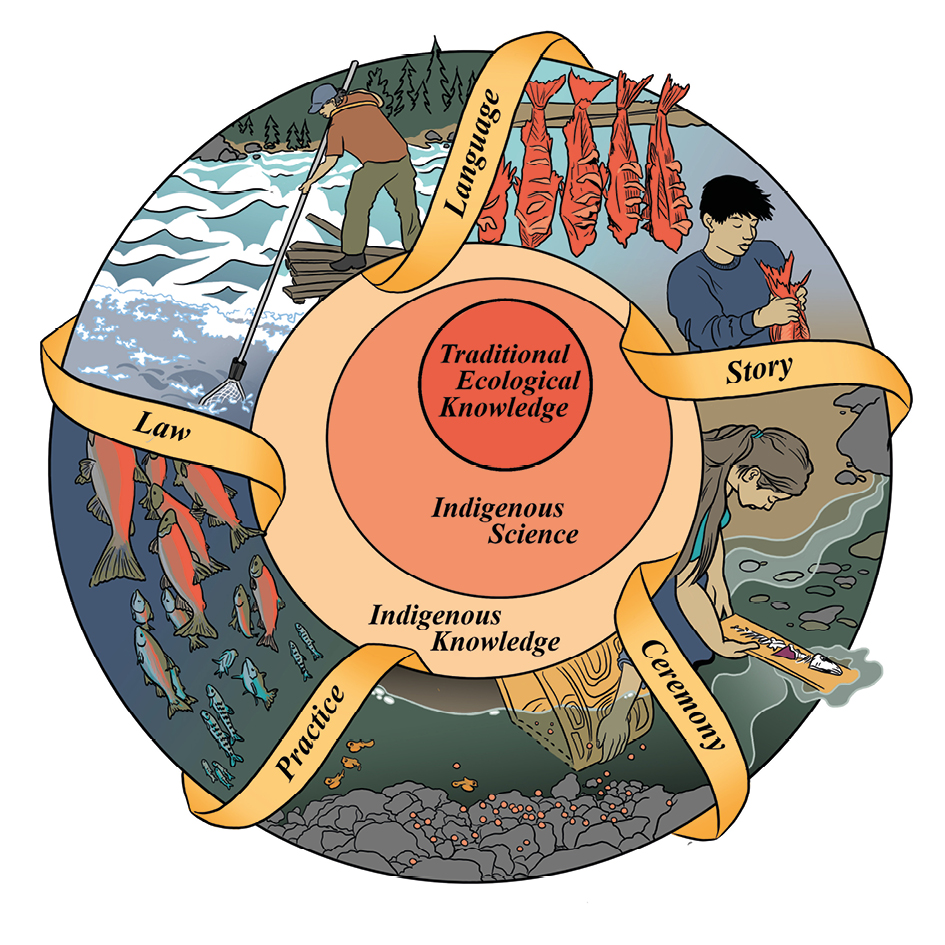

For millennia, Indigenous communities across the globe have cultivated a profound and intricate relationship with the natural world. This connection is not merely spiritual or cultural; it is deeply rooted in their foodways – the practices, knowledge, and beliefs surrounding the production, preparation, and consumption of food. Indigenous food systems are not static relics of the past, but dynamic, living traditions that embody centuries of accumulated Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). TEK, in essence, is the comprehensive understanding of the environment that has been developed by Indigenous peoples through generations of direct contact with the land, water, and sky. It is a holistic system of knowledge that encompasses not only the identification of plants and animals but also their life cycles, their interactions with other species, and their seasonal availability, all understood within a framework of deep respect and reciprocity.

The significance of Indigenous foodways extends far beyond mere sustenance. They are inextricably linked to cultural identity, spiritual practices, social cohesion, and ecological stewardship. The foods that Indigenous peoples cultivate, hunt, gather, and fish are imbued with meaning, telling stories of their ancestors, their lands, and their cosmology. Rituals and ceremonies often revolve around harvests, hunts, or the preparation of specific foods, reinforcing cultural bonds and passing down vital knowledge to younger generations. Moreover, the sustainable management practices inherent in TEK have historically ensured the long-term health and biodiversity of ecosystems, a stark contrast to many modern, extractive agricultural models.

The Pillars of Indigenous Foodways: A Tapestry of TEK

Indigenous food systems are remarkably diverse, reflecting the vast array of environments and cultures they encompass. However, several core principles and practices underscore their commonality:

-

Deep Understanding of Local Ecosystems: TEK provides an unparalleled understanding of the intricate relationships within specific ecosystems. This includes knowing the soil types, water cycles, weather patterns, and the phenology (seasonal timing) of plants and animals. For example, knowledge of when specific berries ripen, when certain fish spawn, or when particular game animals are most abundant allows for sustainable harvesting and ensures continued availability. This is not simply empirical observation; it is often accompanied by a spiritual understanding of the interconnectedness of all life.

-

Biodiversity and Resilience: Indigenous food systems are typically characterized by a high degree of biodiversity. Instead of monocultures, they often feature a diverse array of native plants, cultivated in polyculture systems or integrated into natural landscapes. This biodiversity enhances ecosystem resilience, making them less vulnerable to pests, diseases, and climate fluctuations. The preservation of heirloom seeds and landraces is a crucial aspect of this, ensuring genetic diversity for future food security.

-

Seasonal and Cyclical Harvesting: TEK emphasizes harvesting in harmony with natural cycles. This means understanding when to plant, when to harvest, and how much to take to ensure the regeneration of resources. Practices like fallowing fields, rotating crops, and selective harvesting are integral to maintaining soil health and preventing overexploitation. This approach stands in stark contrast to industrial agriculture, which often depletes resources and relies heavily on external inputs.

-

Holistic Resource Management: Indigenous peoples often view themselves not as owners of the land, but as stewards. Their management practices are guided by a deep sense of responsibility to future generations and to the natural world itself. This can include techniques like controlled burning to promote the growth of certain plants, maintaining healthy fish populations through selective fishing, or managing wildlife populations through respectful hunting practices.

-

Knowledge Transmission and Cultural Preservation: TEK is not static; it is a living body of knowledge that is continuously transmitted through oral traditions, storytelling, practical demonstrations, and ceremonies. Elders play a pivotal role in this transmission, sharing their wisdom with younger generations, ensuring the continuation of cultural practices and ecological understanding.

-

Adaptability and Innovation: While deeply rooted in tradition, Indigenous foodways are also remarkably adaptable. Indigenous communities have historically responded to environmental changes and introduced species by integrating new resources into their existing knowledge systems and adapting their practices accordingly. This demonstrates a pragmatic and innovative spirit that is essential for long-term survival.

Threats to Indigenous Foodways and TEK

Despite their inherent resilience and profound wisdom, Indigenous foodways and TEK face significant threats in the modern world. Colonization, displacement, and the imposition of Western agricultural models have disrupted traditional practices and undermined Indigenous sovereignty.

-

Loss of Land and Traditional Territories: The dispossession of ancestral lands severs the direct connection between Indigenous peoples and the environments that sustain their foodways. Without access to their traditional territories, the ability to practice traditional harvesting, cultivation, and management becomes severely limited.

-

Cultural Assimilation and Language Loss: The erosion of Indigenous languages and cultural practices can lead to the loss of TEK, as much of this knowledge is embedded within linguistic and cultural frameworks. When traditional stories, songs, and ceremonies are no longer passed down, the intricate understanding of the environment they convey can fade.

-

Introduction of Industrial Agriculture and Processed Foods: The widespread adoption of industrial agricultural practices and the influx of processed, non-traditional foods have had a detrimental impact on Indigenous health and dietary patterns. This often leads to increased rates of diet-related diseases, such as diabetes and obesity, while simultaneously displacing traditional, nutrient-dense foods.

-

Climate Change: The global climate crisis disproportionately affects Indigenous communities, disrupting traditional growing seasons, altering wildlife migration patterns, and impacting the availability of traditional foods. Indigenous peoples, who have often been at the forefront of environmental stewardship, are now facing the consequences of a changing climate that threatens their very food systems.

-

Lack of Recognition and Support: In many cases, TEK is not recognized or valued by mainstream scientific and policy-making bodies. This marginalization can hinder efforts to protect Indigenous food systems and incorporate their valuable knowledge into broader conservation and food security initiatives.

The Path Forward: Revitalization and Reconciliation

Recognizing the profound value of Indigenous foodways and TEK is crucial for building more sustainable, equitable, and resilient food systems for all. Revitalization efforts are underway in many Indigenous communities, driven by a deep commitment to preserving their heritage and ensuring their future.

-

Land Back and Indigenous Food Sovereignty: The movement for "Land Back" is central to revitalizing Indigenous foodways. Regaining control over ancestral lands allows Indigenous communities to re-establish traditional food systems, practice TEK, and assert their right to food sovereignty – the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.

-

Intergenerational Knowledge Transfer: Initiatives focused on connecting elders with youth are vital for ensuring the continuation of TEK. This can involve mentorship programs, language immersion initiatives, and hands-on learning experiences in traditional food practices.

-

Documentation and Dissemination of TEK: While TEK is often oral, efforts to respectfully document and share this knowledge, with the consent and guidance of Indigenous communities, can help to preserve it and make it accessible for broader learning and application.

-

Integration of TEK into Policy and Research: There is a growing recognition of the need to integrate TEK into scientific research, conservation efforts, and food policy. This collaboration can lead to more effective and culturally relevant solutions for environmental challenges and food security.

-

Support for Indigenous Food Businesses and Initiatives: Empowering Indigenous entrepreneurs and supporting community-led food initiatives, such as traditional gardens, farmers’ markets, and wild food enterprises, can help to strengthen Indigenous food systems and create economic opportunities.

A Glimpse into Indigenous Recipes: A Celebration of Nature’s Bounty

While it is impossible to capture the entirety of Indigenous culinary traditions in a few recipes, the following examples offer a glimpse into the ingenuity, respect for ingredients, and connection to the land that define these foodways. These recipes are often adapted and vary greatly between nations and regions.

Recipe 1: Pemmican (A Plains Indigenous Staple)

Pemmican is a nutrient-dense, non-perishable food that was historically vital for survival, particularly for Plains Indigenous peoples. It is a testament to their understanding of food preservation and resource utilization.

Ingredients:

- 1 lb lean dried meat (traditionally bison, venison, or elk, dried and pounded into a fine powder)

- 1/2 cup rendered animal fat (traditionally bison tallow, but beef or pork lard can be used)

- 1/2 cup dried berries (traditionally chokecherries, blueberries, or cranberries, ground into a coarse powder)

- Optional: A pinch of salt (used sparingly in traditional preparations)

Instructions:

- Prepare the Dried Meat: If not already powdered, pound the dried meat in a mortar and pestle or place it in a sturdy bag and pound it with a heavy object until it is a fine powder.

- Combine Ingredients: In a bowl, thoroughly mix the dried meat powder with the rendered fat. The fat acts as a binder and preservative.

- Add Berries: Stir in the ground dried berries. The berries add flavor, sweetness, and additional nutrients.

- Mix and Form: Mix everything until it is well combined and has a consistency that can be molded.

- Shape and Store: Press the mixture into cakes or balls. Traditionally, pemmican was often wrapped in animal hides or packed into bags for storage. It can be stored in an airtight container in a cool, dry place for a long time.

TEK Connection: This recipe demonstrates a deep understanding of food preservation through drying and the use of fat as a natural preservative. The combination of protein, fat, and carbohydrates makes it a highly efficient and sustaining food source.

Recipe 2: Three Sisters Stew (Haudenosaunee Tradition)

The "Three Sisters" – corn, beans, and squash – represent a foundational agricultural system for many Indigenous peoples of North America, particularly the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois). They are planted together, with each crop benefiting the others. This stew celebrates this harmonious planting system.

Ingredients:

- 1 cup dried corn (or 2 cups fresh corn kernels)

- 1 cup dried kidney beans (or other native bean variety), soaked overnight and cooked until tender

- 1 medium butternut squash (or other winter squash), peeled, seeded, and cubed

- 1 onion, chopped

- 2 cloves garlic, minced

- 4 cups vegetable broth (or water)

- 1/4 cup chopped fresh herbs (such as wild leeks/ramps, parsley, or thyme)

- Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

- Optional: A drizzle of maple syrup for sweetness

Instructions:

- Sauté Aromatics: In a large pot or Dutch oven, sauté the chopped onion in a little oil or rendered fat over medium heat until softened. Add the minced garlic and cook for another minute until fragrant.

- Add Vegetables and Broth: Add the cubed squash, cooked beans, and corn (if using fresh). Pour in the vegetable broth or water.

- Simmer: Bring the stew to a boil, then reduce heat and simmer, covered, for 20-30 minutes, or until the squash is tender. If using dried corn, add it earlier in the cooking process to ensure it becomes tender.

- Add Herbs and Season: Stir in the chopped fresh herbs. Season with salt and pepper to taste. If desired, add a drizzle of maple syrup for a touch of sweetness.

- Serve: Ladle the stew into bowls and serve hot.

TEK Connection: This recipe highlights the synergistic relationship of the Three Sisters. Corn provides a stalk for beans to climb, beans fix nitrogen in the soil, and squash’s large leaves shade the ground, suppressing weeds and retaining moisture. The stew showcases the versatility of these staple crops and the use of fresh, seasonal ingredients.

Recipe 3: Wild Rice Salad with Cranberries and Pecans (Anishinaabe Inspired)

Wild rice is a sacred grain for many Anishinaabe communities, harvested sustainably from lakes and rivers. This salad celebrates its nutty flavor and its traditional accompaniment of berries and nuts.

Ingredients:

- 1 cup wild rice, rinsed

- 2 cups water or vegetable broth

- 1/2 cup dried cranberries

- 1/2 cup toasted pecans or walnuts, roughly chopped

- 1/4 cup finely chopped red onion

- 2 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley or dill

- Dressing:

- 3 tablespoons olive oil (or a neutral oil)

- 1 tablespoon apple cider vinegar or lemon juice

- 1 teaspoon maple syrup

- Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

Instructions:

- Cook Wild Rice: Combine the rinsed wild rice and water or broth in a saucepan. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat, cover, and simmer for 40-50 minutes, or until the rice is tender and has "split" open. Drain any excess liquid.

- Prepare Dressing: While the rice is cooking, whisk together the olive oil, vinegar or lemon juice, maple syrup, salt, and pepper in a small bowl.

- Combine Salad Ingredients: In a medium bowl, combine the cooked and cooled wild rice, dried cranberries, toasted pecans or walnuts, chopped red onion, and fresh herbs.

- Toss and Serve: Pour the dressing over the salad and toss gently to combine. Serve chilled or at room temperature.

TEK Connection: This recipe honors the sustainable harvesting of wild rice, a practice deeply intertwined with TEK and cultural traditions. The inclusion of cranberries and nuts reflects the availability of wild foods and the knowledge of their complementary flavors and nutritional benefits.

Conclusion

Indigenous foodways and Traditional Ecological Knowledge are not merely historical footnotes but vital, living systems that hold profound lessons for contemporary challenges. They offer a blueprint for sustainable living, a model of ecological stewardship, and a deep understanding of our interconnectedness with the natural world. By recognizing, respecting, and supporting the revitalization of these traditions, we not only honor the enduring wisdom of Indigenous peoples but also pave the way for a more just, resilient, and nourishing future for all. The sustaining roots of Indigenous foodways offer a path forward, reminding us that true nourishment comes from a place of deep respect for the earth and all its inhabitants.