Absolutely! Here’s an article about Wampanoag traditional Thanksgiving foods, aiming for around 1200 words, along with recipe suggestions.

Beyond the Cranberry Sauce: Rediscovering the True Flavors of the Wampanoag Thanksgiving

The narrative of Thanksgiving, as it’s often told, is deeply ingrained in the American psyche. It conjures images of Pilgrims and Native Americans sharing a bountiful harvest feast, a moment of supposed peace and unity that laid the foundation for a nation. However, this popular portrayal, while cherished, often simplifies a complex history and, more importantly, overlooks the vital contributions and distinct culinary traditions of the Wampanoag people, the indigenous inhabitants of the land where this pivotal event took place.

To truly understand the "First Thanksgiving," we must shift our focus from a romanticized myth to a more historically grounded appreciation of the Wampanoag’s way of life, particularly their diet. Their relationship with the land was one of deep respect and intricate knowledge, a symbiosis that provided sustenance through a diverse array of foods, harvested and prepared with methods honed over centuries. The feast shared in 1621, while significant, was not a singular event born of a need for shared survival but rather a reflection of existing Wampanoag hospitality and their accustomed abundance.

A Culinary Landscape Shaped by Land and Season

The Wampanoag, whose name translates to "People of the First Light," inhabited the region of present-day southeastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Their environment was rich and varied, offering coastal bounty, fertile river valleys, and abundant woodlands. This geographical diversity directly translated into a rich and varied diet. Their culinary practices were intrinsically linked to the seasons, with a deep understanding of when to plant, harvest, hunt, and fish.

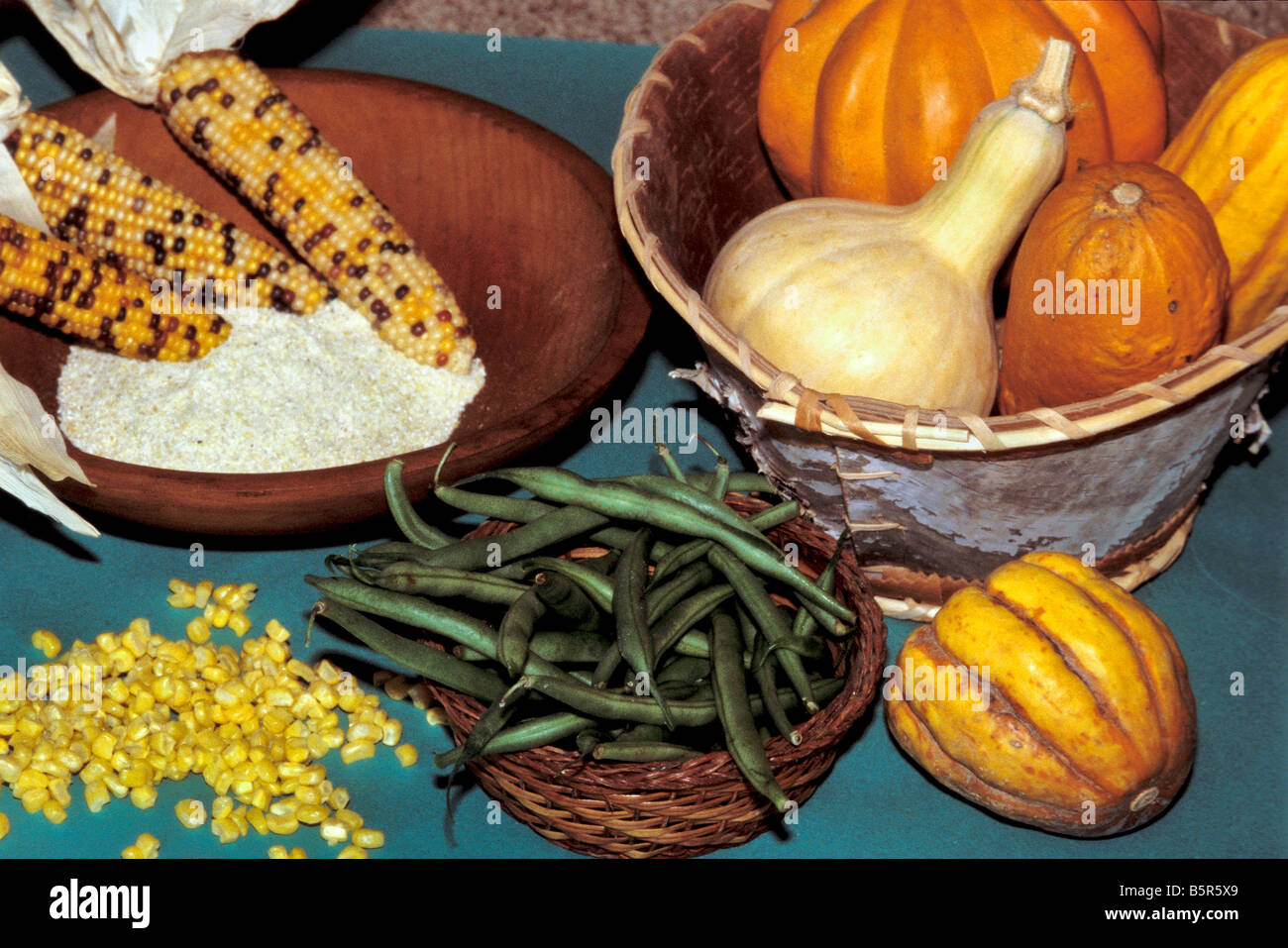

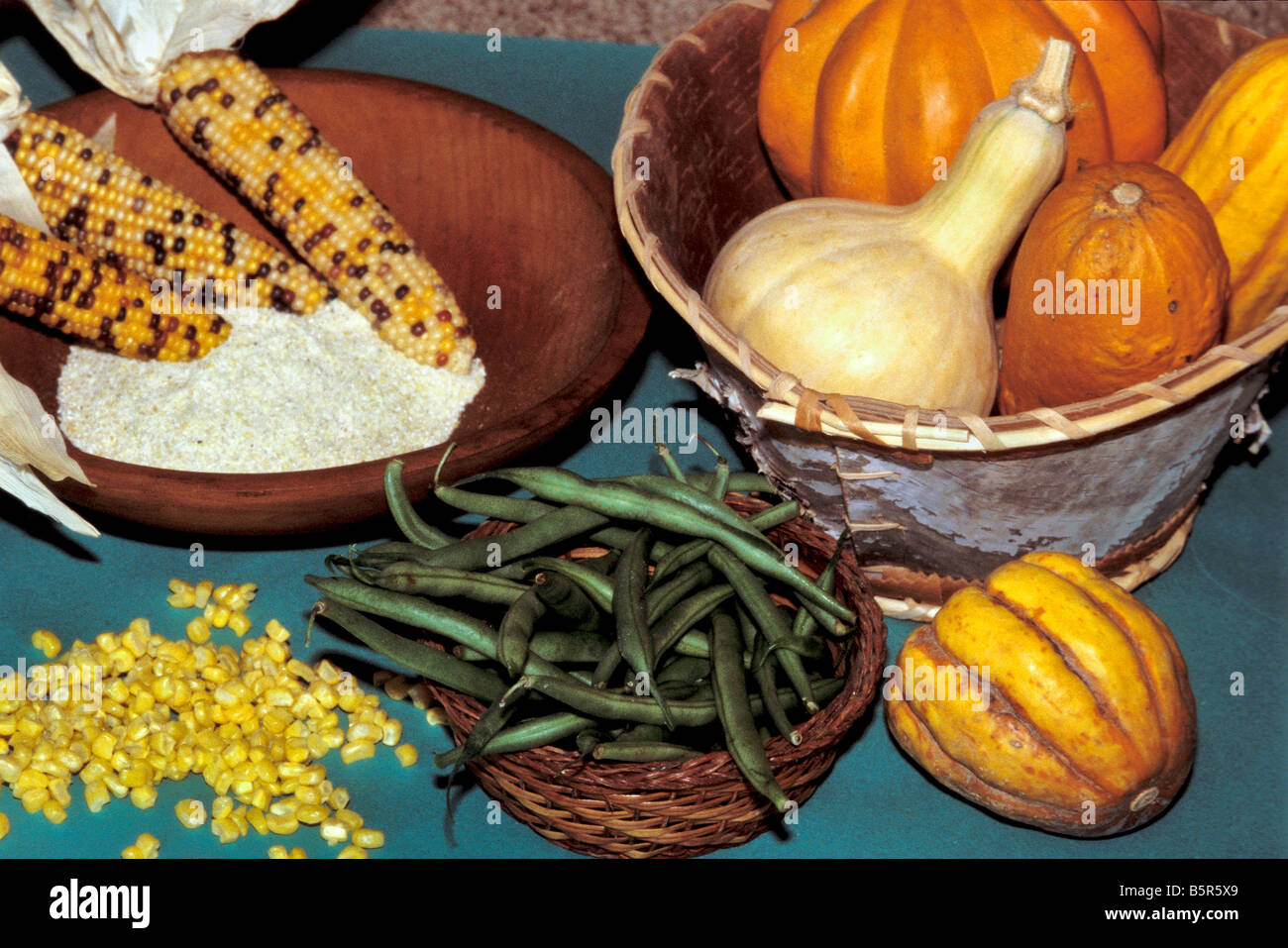

Unlike the European diet, which was heavily reliant on grains like wheat and rye, the Wampanoag staple was corn (maize). Corn was not just a food source; it was a cornerstone of their culture, economy, and spirituality. It was cultivated through sophisticated agricultural techniques, including the "three sisters" method, where corn, beans, and squash were planted together. The corn stalk provided support for the climbing beans, while the beans fixed nitrogen in the soil, nourishing the squash. The squash’s broad leaves, in turn, shaded the ground, retaining moisture and suppressing weeds. This ingenious system maximized yield and promoted soil health, a testament to their advanced understanding of ecology.

Corn was prepared in countless ways. Samp, a coarsely ground cornmeal, was a staple, often boiled into a thick porridge. Hominy, corn that had been treated with an alkali solution (a process called nixtamalization, which unlocks nutrients and improves digestibility), was another common preparation. This was also boiled and could be eaten as a porridge or ground into flour. Cornbread or johnnycakes, made from cornmeal and water or sometimes mixed with animal fat, were also part of their diet. Imagine warm, hearty cakes cooked over an open fire, a far cry from the fluffy, leavened cornbread we know today.

Beyond corn, the Wampanoag cultivated beans and squash, the other two "sisters." Different varieties of beans, such as kidney beans and lima beans, were dried and stored for year-round consumption. Squash, in its many forms, from acorn to butternut, was roasted, boiled, or dried. Their dried squash could be reconstituted and added to stews, providing sweetness and texture.

The Bounty of the Sea and the Land

The coastal location of the Wampanoag meant that seafood played a significant role in their diet. Fish like cod, bass, and herring were abundant and were caught using nets, traps, and spears. Shellfish, including clams, oysters, and mussels, were also a readily available food source, gathered from the shorelines. These were often steamed, boiled, or roasted.

The woodlands provided a wealth of other food sources. Deer were a primary source of meat, hunted with bows and arrows. Their meat was roasted, stewed, or dried for jerky. Turkey, wild and plentiful, was also a significant game bird. Other game animals like rabbits and squirrels were also hunted.

Nuts and Berries: The Wampanoag were adept foragers. Acorns were gathered, leached to remove tannins, and ground into flour for bread and other preparations. Walnuts, hickory nuts, and chestnuts were also important sources of fat and protein. The forests and fields were also dotted with various berries throughout the warmer months. Strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, and cranberries were eagerly gathered. While cranberries are now synonymous with Thanksgiving, their role in the 1621 feast is debated, with some historians suggesting they were likely present, perhaps mashed or stewed, but not necessarily in the sweet, jellied form we recognize.

Seasonings and Preparations

The Wampanoag diet was characterized by its simplicity and reliance on natural flavors. They did not use the extensive array of spices that Europeans were accustomed to. Instead, they relied on the inherent tastes of the ingredients, enhanced by cooking methods like roasting over open fires, boiling in pots made of clay or animal stomachs, and smoking for preservation.

Herbs and roots played a role in flavoring. Wild onions, garlic, and various edible roots were likely used to add depth to their dishes. Maple syrup, tapped from maple trees in the spring, provided a natural sweetener and was likely used sparingly.

Understanding the 1621 Feast

The harvest celebration of 1621, as described by Edward Winslow, a prominent member of the Plymouth colony, was a three-day event. It was initiated by the Pilgrims who had experienced a successful harvest and were celebrating their survival. However, it was the Wampanoag, led by Massasoit, who brought the bulk of the food to the gathering. Winslow notes that Massasoit and his men "for three days… entertained and feasted us." The food they brought likely consisted of venison (deer meat) and fowl (wild birds, possibly including turkey). The presence of corn and squash is also highly probable, given their staple status.

It’s crucial to remember that this was not a feast in the modern sense, with meticulously planned courses and elaborate presentations. It was a gathering, a sharing of resources and hospitality. The Wampanoag were accustomed to such communal meals and feasts, which were an integral part of their social and spiritual life. Their presence and contribution were not an act of newfound alliance but a continuation of their established practices.

Reclaiming the Wampanoag Culinary Heritage

Today, there’s a growing movement to reclaim and celebrate the true culinary heritage of the Wampanoag people. This involves moving beyond the stereotypical Thanksgiving menu and exploring the rich tapestry of foods that sustained them for generations. It’s about understanding the ingenuity of their agricultural practices, the diversity of their foraging, and the deep connection they held with their environment.

For those interested in experiencing these flavors, the focus should be on whole, unprocessed ingredients, prepared with simple techniques. Think about the earthy sweetness of roasted squash, the hearty texture of corn-based dishes, the savory richness of game meats, and the bright tang of wild berries.

Recipe Suggestions: A Taste of Wampanoag Tradition

While precise recipes from 1621 are elusive due to the oral tradition and the nature of historical record-keeping, we can draw inspiration from historical accounts and modern Wampanoag culinary practices to create dishes that honor their traditions. These are not exact replicas but interpretations that aim to capture the essence of their diet.

1. Samp Porridge (A Wampanoag Staple)

This is a basic and nourishing dish.

- Ingredients:

- 1 cup coarsely ground dried corn (samp or hominy grits)

- 4 cups water (or more, depending on desired consistency)

- Pinch of salt (optional, as traditional diets were often less reliant on salt)

- Optional: a drizzle of maple syrup or a small amount of animal fat for richness.

- Instructions:

- Rinse the samp under cold water.

- In a pot, combine the samp and water.

- Bring to a boil, then reduce heat to low, cover, and simmer for at least 1.5 to 2 hours, or until the samp is tender and has reached a thick porridge consistency. Stir occasionally to prevent sticking.

- If the porridge becomes too thick, add more water.

- Season with a pinch of salt if desired. Serve warm, perhaps with a touch of maple syrup.

2. Roasted Acorn Squash with Maple Glaze

A nod to the use of squash and maple.

- Ingredients:

- 1 acorn squash, halved and seeds removed

- 1 tablespoon olive oil or melted animal fat

- 2 tablespoons pure maple syrup

- Pinch of salt and pepper (optional)

- Instructions:

- Preheat oven to 400°F (200°C).

- Brush the cut sides of the acorn squash with olive oil or fat. Season with salt and pepper if using.

- Place the squash cut-side down on a baking sheet.

- Roast for 30-40 minutes, or until tender when pierced with a fork.

- Remove from oven. Flip the squash halves so they are cut-side up.

- Drizzle the maple syrup into the cavities of the squash.

- Return to the oven for another 5-10 minutes, allowing the glaze to caramelize slightly.

- Serve warm.

3. Venison Stew with Root Vegetables

A hearty stew reflecting the importance of game meat.

- Ingredients:

- 1 lb venison stew meat, cut into 1-inch cubes

- 1 tablespoon olive oil or animal fat

- 1 onion, chopped

- 2 carrots, chopped

- 2 parsnips or turnips, chopped

- 2 cloves garlic, minced (optional)

- 4 cups beef or venison broth

- 1 bay leaf

- Salt and pepper to taste

- Optional: A handful of dried berries (like cranberries or blueberries) for a touch of tartness.

- Instructions:

- Pat the venison dry and season with salt and pepper.

- Heat olive oil or fat in a large pot or Dutch oven over medium-high heat. Brown the venison in batches, then remove and set aside.

- Add the chopped onion, carrots, and parsnips/turnips to the pot. Sauté until softened, about 5-7 minutes. Add garlic if using and cook for another minute.

- Return the venison to the pot. Add the broth and bay leaf. If using dried berries, add them now.

- Bring to a boil, then reduce heat to low, cover, and simmer for at least 2-3 hours, or until the venison is very tender.

- Season with additional salt and pepper to taste. Remove the bay leaf before serving. Serve hot.

4. Corn and Bean Cakes (Inspired by Johnnycakes)

A simple and versatile preparation of their staple crops.

- Ingredients:

- 1 cup cornmeal (medium grind)

- 1/2 cup cooked mashed beans (e.g., kidney beans or pinto beans)

- 1/4 cup water (or more, as needed)

- Pinch of salt (optional)

- 1-2 tablespoons animal fat or oil for cooking

- Instructions:

- In a bowl, combine the cornmeal, mashed beans, and salt (if using).

- Gradually add water, mixing until you have a thick batter that holds its shape. It should not be too wet.

- Heat the fat or oil in a skillet over medium heat.

- Spoon the batter into the skillet to form small, flat cakes, about 2-3 inches in diameter.

- Cook for 3-5 minutes per side, until golden brown and cooked through.

- Serve warm, perhaps with a side of stew or simply on their own.

Conclusion

The story of Thanksgiving is incomplete without acknowledging the profound culinary contributions of the Wampanoag people. Their diet was a testament to their intimate knowledge of the natural world, their agricultural prowess, and their deep cultural connection to the foods that sustained them. By exploring and celebrating these traditional foods, we can gain a more authentic and respectful understanding of the events of 1621 and honor the enduring legacy of the Wampanoag, the People of the First Light. This Thanksgiving, consider venturing beyond the familiar and savoring the true flavors of indigenous American cuisine.