The Acorn’s Bounty: Sustaining California’s Native Peoples Through Ancient Preparation

For millennia, the sprawling oak woodlands of California have been the lifeblood of its Indigenous peoples. Among the most vital and culturally significant resources provided by these majestic trees are their acorns. More than just a food source, acorns represent a deep connection to the land, a testament to intricate ecological knowledge, and the foundation of a complex and nourishing diet. The preparation of acorns is a sophisticated process, honed over countless generations, that transforms a potentially bitter and indigestible nut into a versatile and highly nutritious staple. This article delves into the traditional methods of acorn preparation employed by California Native American tribes, exploring the science behind their techniques, the cultural significance of this process, and the enduring legacy of acorn cuisine.

The sheer abundance and nutritional value of acorns made them an indispensable food for many California tribes, including the Chumash, Miwok, Pomo, Yokuts, and many others. These nuts are rich in carbohydrates, healthy fats, protein, and essential minerals like potassium, calcium, and magnesium. However, acorns contain significant amounts of tannins, bitter-tasting compounds that can be toxic in large quantities and make the nuts unpalatable and difficult to digest. The genius of Native Californian acorn preparation lies in its effective and efficient removal of these tannins, unlocking the nutritional potential of this abundant resource.

The Crucial Step: Leaching the Tannins

The cornerstone of all acorn preparation is the process of leaching, which involves removing the tannins. This was achieved through various methods, primarily water-based leaching. The specific techniques varied depending on the tribe, the type of acorn, and the available resources.

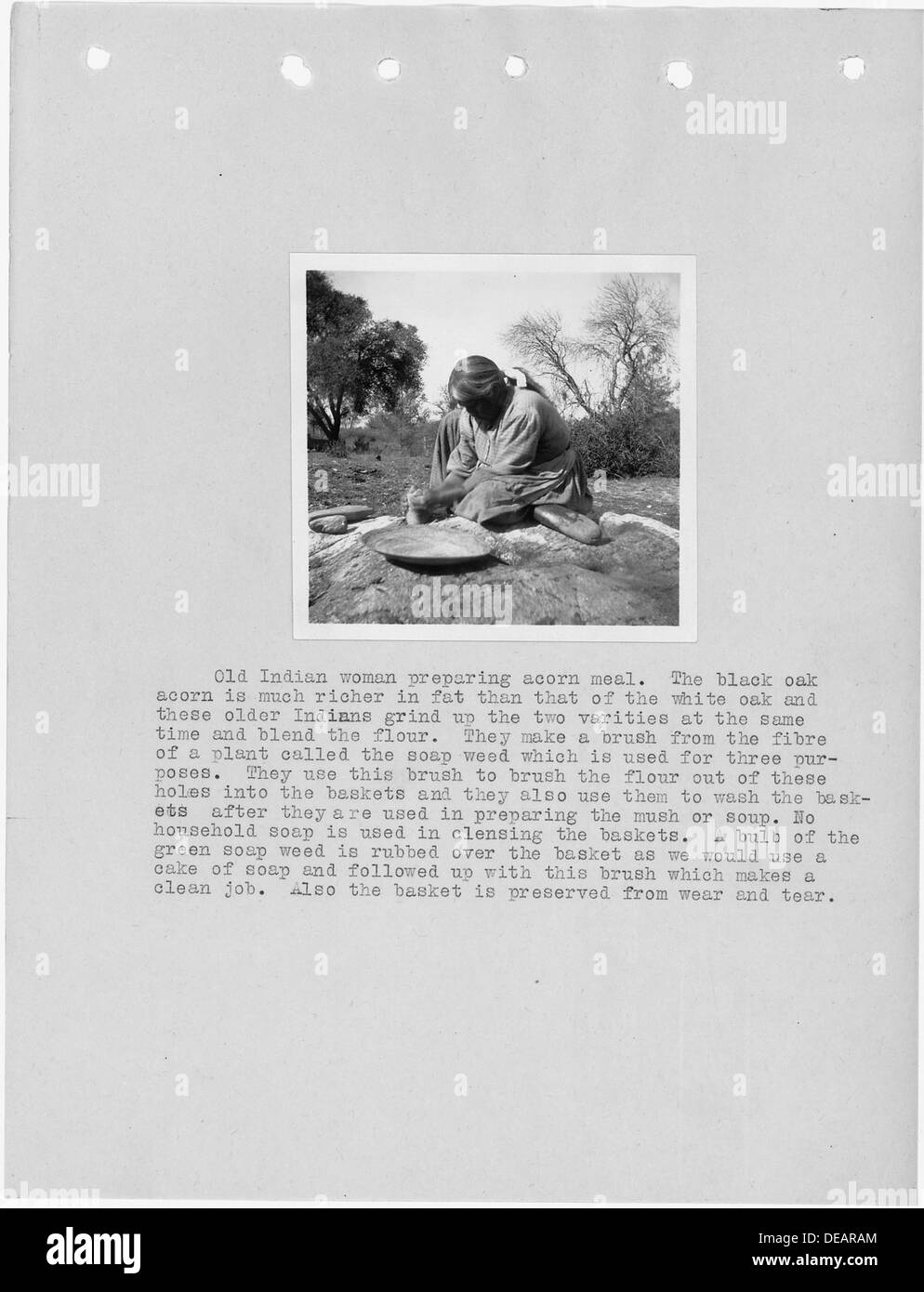

- Grinding and Leaching: The most common method involved grinding the acorns into a fine meal. Traditionally, this was done using a mortar and pestle, often large bedrock mortars found throughout ancestral territories. The acorn meal was then placed in a permeable container or directly onto a sandy or gravelly surface.

- Basket Leaching: Many tribes utilized finely woven leaching baskets. These baskets, crafted with remarkable skill from materials like willow or sedge, were designed with a tight weave to hold the acorn meal while allowing water to pass through. The basket, filled with acorn meal, would be placed in a stream or on a sloped surface where water could be repeatedly poured over it. The flowing water would gradually dissolve and carry away the tannins.

- Sand/Gravel Leaching: Another effective method involved spreading the acorn meal thinly on a sandy or gravelly area, often near a water source. Water would be poured over the meal, and the tannins would leach into the surrounding soil and be carried away by natural drainage. This method required careful observation and replenishment of the meal as it was leached.

- Clay-Lined Pits: Some tribes employed clay-lined pits for leaching. The acorn meal would be placed in the pit, and water would be added. The clay lining helped to contain the meal and prevent excessive loss.

The duration of leaching was critical and varied. It could take anywhere from a few hours to several days, depending on the type of acorn (some species, like the California Black Oak, have higher tannin content than others, such as the Valley Oak), the fineness of the grind, and the volume of water used. Tribes developed an intimate understanding of how to test for the absence of tannins. A small amount of leached acorn meal would be tasted; if it was no longer bitter, the leaching process was complete.

Transforming the Leached Meal: From Raw Ingredient to Staple Food

Once leached, the acorn meal was transformed into a variety of nourishing foods. The texture and moisture content of the leached meal were key factors in determining the preparation method.

-

Acorn Flour/Meal: The most basic form was the leached acorn flour or meal. This dry, flour-like substance could be stored for long periods, providing a crucial food reserve for leaner times. It served as the base for numerous dishes.

-

Acorn Gruel/Porridge: A common and easily digestible dish was acorn gruel or porridge. The leached acorn meal was mixed with water and cooked into a thick, creamy consistency. This was often a breakfast food or a comforting meal for the young, elderly, or infirm.

-

Acorn Bread/Cakes: This is perhaps the most iconic acorn preparation. Leached acorn meal was mixed with water to form a dough. This dough was then shaped into flat cakes or loaves and cooked.

- Baking on Hot Stones: A prevalent method involved baking acorn cakes directly on hot stones. Large, flat stones were heated in a fire, and the acorn dough was placed on them to cook. This resulted in a dense, flavorful bread with a slightly crispy exterior.

- Baking in Ashes: In some instances, acorn cakes were wrapped in large leaves (like bay or maple) and then buried in hot ashes. This method provided a gentler, more even cooking.

- Steaming: Acorn dough could also be steamed, often in tightly woven baskets placed over boiling water. This produced a softer, moister bread.

-

Acorn Mush/Hominy: Similar to gruel, but often with a coarser texture. This could be a more substantial meal, sometimes incorporating other ingredients like seeds or berries.

-

Acorn Paste: A thicker, richer preparation. The leached acorn meal was mixed with water to create a dense paste. This paste could be eaten directly, used as a filling for other foods, or further processed.

Beyond the Basics: Culinary Innovations and Regional Variations

The ingenuity of California Native American acorn preparation extended to incorporating other ingredients and developing specialized dishes.

-

Sweeteners: While acorns themselves are not sweet, tribal peoples understood how to add natural sweeteners. Honey from native bees was a prized ingredient, used to sweeten acorn gruels, breads, and pastes. Manzanita berries, with their naturally tart and slightly sweet flavor, were also sometimes incorporated.

-

Fats and Proteins: To enhance the nutritional profile and flavor, leached acorn meal was often combined with animal fats or proteins. This could include rendered animal fat (deer, elk, bear) or finely ground dried fish or shellfish. These additions made acorn dishes more filling and provided a complete protein source.

-

Flavor Enhancements: Wild seeds, berries (like elderberries or blackberries), and even certain edible greens were sometimes added to acorn preparations to add complexity and flavor. Smoked fish or meat could also be ground and incorporated.

-

Acorn "Tamales": Some tribes, particularly those with connections to Mesoamerican culinary traditions, developed acorn dishes akin to tamales. Leached acorn meal was mixed with fats and seasonings, wrapped in leaves, and steamed.

-

"Acorn Coffee" or Broth: The water used for leaching, especially from acorns with lower tannin content, could be consumed as a mild, nutrient-rich broth. Some tribes would boil leached acorn meal with water for extended periods to create a savory liquid.

The Science Behind the Tradition

The effectiveness of tannin leaching is rooted in basic chemistry. Tannins are polyphenolic compounds that bind to proteins. Water acts as a solvent, dissolving these compounds and carrying them away from the acorn meal. The fineness of the grind is crucial because it increases the surface area of the acorn meal, allowing water to penetrate more effectively and leach the tannins more efficiently. Different acorn species have varying chemical compositions, leading to variations in tannin levels and thus requiring slightly different leaching times and techniques.

Cultural Significance and Enduring Legacy

The preparation of acorns was not merely a culinary chore; it was a deeply ingrained cultural practice, interwoven with social structures, spiritual beliefs, and ecological stewardship.

-

Community and Cooperation: Acorn gathering and processing were often communal activities, fostering cooperation and strengthening social bonds. Women, in particular, played a central role in the meticulous work of grinding, leaching, and cooking.

-

Knowledge Transmission: The intricate knowledge of acorn species, their habitats, optimal harvesting times, and preparation techniques was passed down orally from generation to generation, ensuring the continuity of this vital food source.

-

Connection to the Land: The reliance on acorns fostered a profound respect for oak trees and the ecosystems they supported. Native peoples understood the cycles of the oaks, practiced sustainable harvesting, and often engaged in practices that promoted oak health and regeneration.

-

Ceremony and Spirituality: Acorn feasts and ceremonies were common, celebrating the bounty of the harvest and acknowledging the spiritual significance of the oak tree. Acorns were sometimes used in symbolic offerings or rituals.

-

Resilience and Survival: The ability to effectively prepare and store acorns provided a buffer against famine and allowed Native Californian populations to thrive for millennia. This traditional knowledge was a testament to their resilience and adaptability.

Modern Echoes of an Ancient Practice

While historical pressures and cultural disruptions have impacted traditional acorn preparation, there is a growing movement to revive and reintroduce these ancestral practices. Today, Indigenous communities and allies are working to:

- Educate: Sharing the knowledge of acorn preparation with younger generations and the wider public.

- Replant: Encouraging the planting of native oak trees.

- Reclaim: Integrating acorn-based foods into contemporary diets and culinary traditions.

- Research: Further understanding the nutritional benefits and culinary versatility of acorns.

The acorn, once a cornerstone of California Native American sustenance, is slowly re-emerging as a symbol of cultural pride, ecological wisdom, and a delicious, nutritious food source for the future. The meticulous and ingenious methods developed by these ancient peoples continue to inspire awe and offer valuable lessons in sustainable living and culinary heritage.

California Native American Acorn Recipe Collection

Here are a few simplified recipes inspired by traditional California Native American acorn preparations. It’s important to note that authentic traditional preparation involves careful leaching to remove tannins, which is a crucial step and requires knowledge and practice. These recipes assume you have access to leached acorn flour or meal. If you are attempting to process acorns yourself, thorough research into leaching techniques is paramount.

Important Note on Sourcing Leached Acorn Flour:

- Indigenous Growers/Tribal Communities: The best way to obtain truly traditional, leached acorn flour is to support Indigenous growers or tribal communities who are reviving these practices.

- Specialty Food Stores/Online Retailers: Occasionally, you may find commercially processed, leached acorn flour from specialty food providers. Always inquire about the origin and processing methods.

- DIY (with extreme caution): If you are in an area with abundant native oak trees and have the time and resources, you can research and attempt the leaching process yourself. This is a significant undertaking and requires careful learning and practice. Never consume acorns that have not been properly leached.

1. Simple Acorn Gruel (Miwok-inspired)

This is a basic, comforting porridge that can be eaten as is or sweetened.

Yields: 1-2 servings

Prep time: 5 minutes

Cook time: 10-15 minutes

Ingredients:

- 1/2 cup leached acorn flour

- 1.5 – 2 cups water (adjust for desired consistency)

- Pinch of salt (optional)

- Wild honey or other natural sweetener (optional, for serving)

- Fresh berries or nuts (optional, for serving)

Instructions:

- In a small saucepan, whisk together the leached acorn flour and 1.5 cups of water until smooth and no lumps remain.

- Place the saucepan over medium heat.

- Bring the mixture to a gentle simmer, stirring constantly to prevent sticking.

- Continue to cook and stir for 10-15 minutes, or until the gruel has thickened to your desired consistency. It should be similar to a thick porridge or oatmeal.

- Add more water if it becomes too thick. Stir in a pinch of salt if desired.

- Serve warm. Drizzle with wild honey or your preferred natural sweetener, and top with fresh berries or chopped nuts if desired.

2. Acorn Cakes on Hot Stones (Pomo/Yokuts-inspired)

This recipe simulates baking on hot stones by using a very hot cast-iron skillet or griddle. These are dense, hearty cakes.

Yields: 4-6 small cakes

Prep time: 10 minutes

Cook time: 10-15 minutes

Ingredients:

- 1 cup leached acorn flour

- 1/4 cup water (you may need a little more or less)

- Pinch of salt (optional)

- Rendered animal fat or neutral oil (for greasing the pan)

- Wild honey or berry compote (for serving)

Instructions:

- In a medium bowl, combine the leached acorn flour and salt (if using).

- Gradually add the water, mixing with your hands or a sturdy spoon until a firm, workable dough forms. It should not be sticky. Add more water a teaspoon at a time if needed, or more acorn flour if it’s too wet.

- Divide the dough into 4-6 equal portions and shape them into flat, round cakes, about 1/2 inch thick.

- Heat a cast-iron skillet or griddle over medium-high heat until very hot.

- Lightly grease the hot skillet with a small amount of rendered fat or oil.

- Carefully place the acorn cakes onto the hot skillet.

- Cook for 5-7 minutes per side, or until golden brown and firm. They may puff up slightly.

- Remove from the skillet and let cool slightly.

- Serve warm with a drizzle of wild honey or a side of berry compote.

3. Acorn and Seed Patties (General Native Californian-inspired)

This recipe incorporates wild seeds for added texture and nutrition, a common practice.

Yields: 6-8 small patties

Prep time: 15 minutes

Cook time: 15-20 minutes

Ingredients:

- 1 cup leached acorn flour

- 1/4 cup mixed toasted wild seeds (such as chia, sunflower, or pinion pine nuts, finely ground or chopped)

- 1/4 teaspoon salt (optional)

- 1/3 – 1/2 cup water (adjust for desired consistency)

- Rendered animal fat or neutral oil (for frying)

Instructions:

- In a medium bowl, combine the leached acorn flour, ground seeds, and salt (if using).

- Gradually add the water, mixing until a firm dough forms that can be shaped into patties.

- Divide the dough into 6-8 portions and shape them into small, flattened patties, about 1/2 inch thick.

- Heat a generous amount of rendered fat or oil in a skillet over medium heat.

- Carefully place the acorn and seed patties into the hot fat. Do not overcrowd the pan.

- Fry for 7-10 minutes per side, or until golden brown and cooked through.

- Remove from the skillet and drain on a wire rack or paper towels.

- Serve warm as a savory side dish or a light meal.

4. Sweetened Acorn Paste (Chumash-inspired)

This is a rich, energy-dense paste that can be eaten directly or used as a filling.

Yields: About 1 cup

Prep time: 5 minutes

Cook time: 5-10 minutes

Ingredients:

- 1 cup leached acorn flour

- 1/4 cup water (you may need slightly more or less)

- 2-3 tablespoons wild honey or maple syrup (adjust to taste)

- Pinch of ground cinnamon or other wild spice (optional)

Instructions:

- In a small saucepan, combine the leached acorn flour and water. Stir until a thick paste forms.

- Place the saucepan over low heat and cook, stirring constantly, for 5-10 minutes until the paste thickens further and becomes slightly glossy.

- Remove from heat and stir in the wild honey or maple syrup until fully incorporated.

- Add a pinch of cinnamon or other spice if desired.

- Allow to cool slightly.

- Serve as is, or use as a filling for baked goods or dried fruits. This paste can be stored in the refrigerator for a few days.

These recipes offer a glimpse into the incredible culinary heritage of California Native American peoples, highlighting the versatility and nutritional power of the acorn. Remember to always prioritize authentic sourcing and responsible preparation.