The Sustenance of Self: Indigenous Foodways and the Formation of Cultural Identity

For Indigenous communities across the globe, food is far more than mere sustenance. It is a profound and intricate tapestry woven from threads of history, spirituality, community, and identity. Indigenous foodways, the complex systems of knowledge, practices, and beliefs surrounding the production, preparation, and consumption of food, serve as a cornerstone for the formation and perpetuation of cultural identity. In a world increasingly shaped by globalization and assimilation, understanding and revitalizing these traditional food practices are crucial for the survival and flourishing of Indigenous cultures.

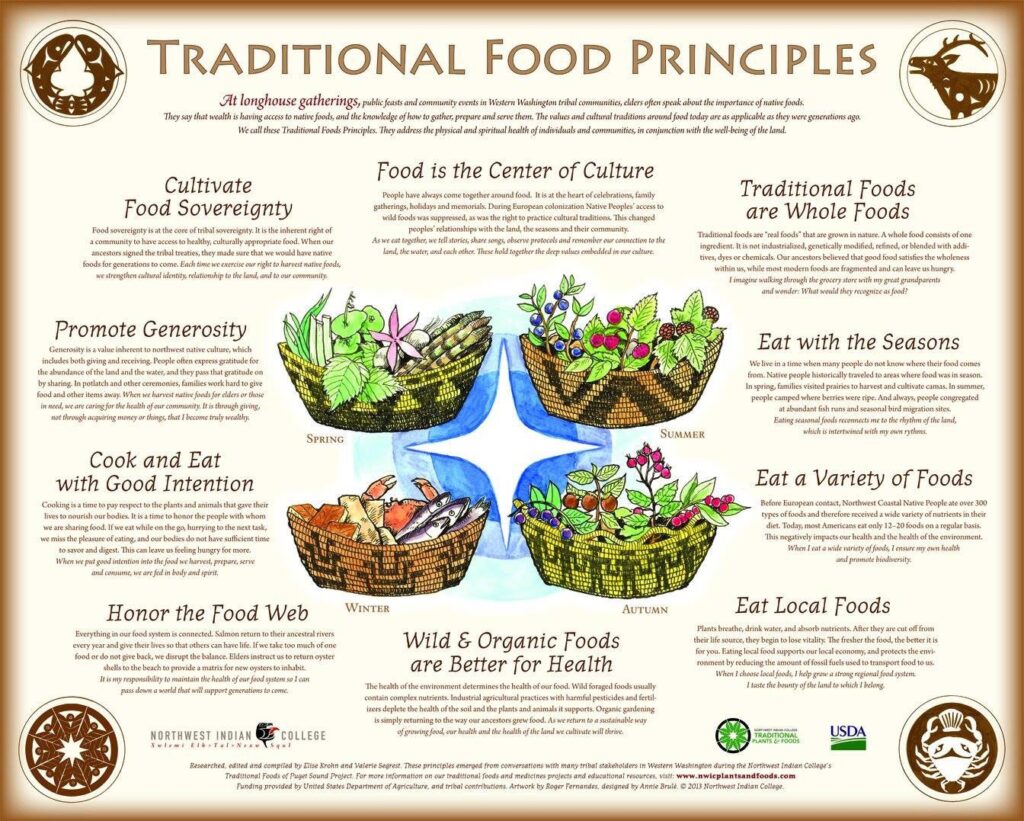

At its core, Indigenous food is intrinsically linked to the land and its ecosystems. Traditional diets were, and in many cases still are, dictated by the bounty and rhythms of specific geographical locations. The plants that grow, the animals that roam, the fish that swim – these elements are not just resources but kin, imbued with spiritual significance and respect. The knowledge of how to harvest sustainably, when to gather, and how to utilize every part of an animal or plant is passed down through generations, forming a deep, reciprocal relationship between people and their environment. This intimate connection fosters a sense of belonging and rootedness, vital components of cultural identity. When an Indigenous person consumes traditional foods, they are not just nourishing their body; they are connecting with their ancestors, their land, and their heritage.

The act of preparing and sharing food is also a powerful social and cultural ritual. Traditional cooking methods, often communal and involving extended family and community members, reinforce social bonds and transmit cultural values. Stories are told around the fire as meals are prepared, elders impart wisdom, and younger generations learn not only culinary skills but also the narratives and histories that accompany each dish. These shared meals are more than just nourishment; they are spaces for cultural transmission, where language, customs, and worldview are actively reinforced. The communal aspect of Indigenous foodways emphasizes interdependence and collective well-being, mirroring the values of many Indigenous societies.

Furthermore, Indigenous foods often carry deep symbolic and spiritual meanings. Certain plants might be associated with healing properties, specific animals with particular spirits or clan totems, and seasonal celebrations are frequently marked by distinct culinary traditions. These symbolic connections elevate food from the mundane to the sacred, embedding it within the spiritual framework of Indigenous life. The preparation of ceremonial foods, for instance, involves specific rituals and prayers, acknowledging the spiritual power of the ingredients and the act of consumption. This spiritual dimension imbues food with a profound significance that directly contributes to a strong sense of self and belonging within a particular cultural context.

The formation of Indigenous cultural identity through food is a dynamic and evolving process. Historically, colonization, forced assimilation policies, and the disruption of traditional lands and lifeways have had a devastating impact on Indigenous food systems. The introduction of processed foods, the loss of traditional knowledge, and the environmental degradation of ancestral territories have led to a decline in the consumption of traditional foods and, consequently, a weakening of cultural identity for many. However, Indigenous peoples are actively engaged in a resurgence of their foodways, recognizing their vital role in cultural revitalization and self-determination.

This resurgence manifests in various ways. There is a growing movement to reclaim ancestral lands and re-establish traditional agricultural practices, such as the cultivation of heirloom crops like maize, beans, and squash, or the sustainable harvesting of wild game and fish. Indigenous communities are also actively documenting and sharing traditional recipes and knowledge, often through community workshops, cookbooks, and digital platforms. This knowledge preservation is crucial for ensuring that future generations can access and benefit from the wisdom of their ancestors.

Moreover, Indigenous chefs and food entrepreneurs are emerging, creatively reinterpreting traditional ingredients and dishes for contemporary audiences. They are not only showcasing the deliciousness and health benefits of Indigenous foods but also using them as a platform to educate, advocate, and celebrate their cultural heritage. These culinary innovators are bridging the gap between tradition and modernity, demonstrating that Indigenous foodways are not static relics of the past but vibrant and adaptable expressions of living culture.

The concept of food sovereignty – the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems – is central to this resurgence. Indigenous food sovereignty empowers communities to control their food systems, ensuring that their traditional foods are accessible, affordable, and culturally relevant. This control is essential for the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples and for the preservation of their distinct cultural identities.

In conclusion, Indigenous foodways are inextricably linked to the formation and perpetuation of cultural identity. They are a testament to the deep relationship between people, land, and spirit. The knowledge, practices, and symbolism embedded within traditional foods provide a powerful sense of belonging, continuity, and self-worth for Indigenous individuals and communities. As Indigenous peoples continue to reclaim and revitalize their food systems, they are not only nourishing their bodies but also strengthening the very essence of their cultural identity, ensuring that their heritage continues to thrive for generations to come.

Indigenous Recipe Listings (Conceptual Examples)

It’s important to note that traditional Indigenous recipes are often passed down orally and can vary significantly between different nations and regions. The following are conceptual examples that highlight common ingredients and preparation styles. For authentic recipes, it is best to consult directly with Indigenous communities and elders.

1. Three Sisters Stew (Haudenosaunee Inspiration)

- Concept: A hearty and nutritious stew featuring the "Three Sisters" – corn, beans, and squash – which are traditionally grown together synergistically.

- Key Ingredients:

- Dried or fresh corn kernels

- Dried or fresh beans (e.g., kidney beans, pinto beans)

- Winter squash (e.g., butternut, acorn), cubed

- Wild game or poultry (optional, e.g., venison, turkey)

- Wild rice or other grains

- Herbs (e.g., wild mint, sage)

- Water or broth

- Preparation Concept: Simmer all ingredients together until tender. The squash provides thickening, the beans protein, and the corn carbohydrates, creating a complete and balanced meal.

2. Smoked Salmon with Wild Berries (Pacific Northwest Inspiration)

- Concept: A classic preparation showcasing the bounty of the Pacific Northwest.

- Key Ingredients:

- Fresh salmon fillets (traditionally smoked over cedar wood)

- Assortment of fresh or dried wild berries (e.g., huckleberries, salmonberries, blueberries)

- Wild greens (e.g., fiddleheads, miner’s lettuce)

- Optional: Juniper berries, cedar salt

- Preparation Concept: The salmon is traditionally smoked for preservation and flavor. Served alongside a fresh berry compote or salad with wild greens.

3. Bannock Bread (Various Indigenous Traditions)

- Concept: A simple, unleavened bread often cooked over a fire or in a skillet.

- Key Ingredients:

- Flour

- Lard or vegetable shortening

- Water or milk

- Salt

- Optional: Baking powder for a lighter texture

- Preparation Concept: Mix ingredients to form a dough, shape into a flatbread or round, and bake or fry until golden brown.

4. Pemmican (Plains Indigenous Traditions)

- Concept: A highly nutritious, calorie-dense food historically used by Plains Indigenous peoples for sustenance during long journeys.

- Key Ingredients:

- Dried, lean meat (e.g., bison, venison), pounded into a powder

- Rendered animal fat (tallow)

- Optional: Dried berries, nuts

- Preparation Concept: The meat powder is mixed with melted fat to create a solid, shelf-stable food. Berries can be added for flavor and additional nutrients.

5. Wild Rice Soup (Great Lakes Indigenous Traditions)

- Concept: A creamy and comforting soup featuring the native wild rice.

- Key Ingredients:

- Wild rice

- Vegetables (e.g., onions, carrots, celery)

- Mushrooms (fresh or dried)

- Broth (vegetable or game)

- Cream or milk (traditionally sometimes a thickening agent like pounded acorn flour was used)

- Herbs (e.g., thyme, parsley)

- Preparation Concept: Cook wild rice until tender. Sauté vegetables and mushrooms, then combine with broth and rice. Finish with cream and herbs.